How Much Cash Do You Really Need To Buy A Home?

To buy a house, you need cash for a down payment…and then some. Here’s a look at the actual amount of money you’ll need on hand at closing to purchase a new home.

One of the biggest shocks of buying a home is finding out that you need way more cash to close on a house than just a down payment. It’s hard enough to save for the down payment on your home, only to find out that you need more—often a lot more—in order to complete the transaction.

Let’s look at how much cash it takes to actually purchase a home. And where possible, suggest ways that can reduce or even eliminate the additional cash requirements.

The actual down payment

This is the only cash outlay in the home-buying process that’s obvious to most buyers. It is usually expressed as a percentage of the purchase price of the property. For example, if the purchase price is $200,000, and you’re required to make a 10 percent down payment, you’ll have to pay $20,000.

That’s the easy part.

How much do you need for a down payment on a house?

It varies. With most lenders, if you want to avoid paying additional private mortgage insurance (PMI), you’re looking at a 20 percent down payment. But coming up with 20 percent may be difficult for many first-time buyers, so mortgage lenders have options with down payments of 10 percent, 5 percent or—if you qualify for special FHA loans or VA mortgage loans—as little as 3.5 percent.

Also Read: How Do You Know When You’re Ready To Buy A Home?

Closing costs

This is where things start to get a little complicated. This is because the cash outlay to make the purchase becomes (often) much higher than the down payment alone.

Closing costs may run up to two to three percent of your loan amount

On a $200,000 mortgage, you’ll need to come up with between $4,000 and $6,000 in addition to your down payment.

Closing costs vary from one state to another. This is due to differences in either the real estate transfer tax, or mortgage “stamps” (government taxes collected based on a percentage of your mortgage loan amount). They can also vary based on different rates charged for appraisals, attorneys, and even title insurance.

Closing costs can also vary from one lender to another, and even from one loan to another. For example, each lender charges a different application fee. In addition, lenders often charge “points”—so named because they represent a percentage point of the loan amount.

An origination fee is one kind of a point. It represents compensation to the lender for placing the loan. Discount points are another type. They represent points paid to lower the mortgage interest rate on a permanent basis.

There are actually two alternatives that can either reduce or completely eliminate closing costs:

Negotiate for the seller to pay your closing costs. This will only be permissible in areas where this is common practice.

Negotiate premium pricing with your lender. This is where you pay a higher interest rate on your mortgage in exchange for the lender paying the closing costs.

Either may be a good option, particularly if you are making a minimum down payment, like five percent and adding closing costs on top would make your cash outlay significantly higher.

Prepaid expenses

These are probably the most confusing charges for home buyers, but they are completely necessary. With most mortgages, the lender will put real estate taxes and homeowner’s insurance in escrow. This means that those charges will be included in your monthly payment, and paid by the lender when due.

In order for that to happen, the lender needs to collect certain amounts upfront, to ensure that the funds are available to make the payments when they are due. The escrow accounts are set up to pay the charges on the next due date, while a portion of your monthly payment replenishes the escrow account for the due date after that.

Depending on where you live, and the frequency of real estate tax collections, the lender may have to put anywhere between two and 12 months of real estate taxes in escrow. If the taxes on the house are $250 per month, and a six-month escrow is required, that will translate to a prepaid expense of $1,500 at closing.

The same applies to insurance.

For homeowner’s insurance policies, you’re typically required to prepay a one-year homeowners insurance policy on the house, plus an extra two months of premium charges to the lender’s escrow account. The lender may also escrow one or two months of premiums for PMI as well if required.

Depending on where you live, prepaid expenses may come to as much as two percent of the loan amount.

Fortunately, you can have some or all of the prepaid expenses paid for you by either the seller or by premium pricing paid to the lender. A third option is to decline the escrow arrangement by the lender. This will require that you make a down payment of at least 20 percent.

Also Read: Newbies Step by Step Guide to Buying a First Home

Utility adjustments

Utility adjustments can include a large number of charges. Luckily, they seldom come to more than a few hundred dollars. They basically represent utility costs paid by property seller in advance.

For example, if a seller fills the heating oil tank just before the closing, you’ll be required to reimburse the seller for the unused oil. This will happen at the closing table. Similar charges can be incurred if the seller has prepaid other utilities, such as water, sewer, or trash removal.

Still another expense that could require adjustment at closing are homeowners association fees. In many homeowners association neighborhoods, member fees are paid on an annual basis. If the seller has paid the fee for the full year, and you’re closing on the house on March 31—three months into the year—you will be required to reimburse the seller for nine months’ worth of fees. There may also be a fee to the HOA to get started. They may call it a transfer fee or something similar. Basically, it’s a lump sum upfront from the new homeowner to get into the HOA.

Since these adjustments are direct expenses, they generally cannot be paid by the seller, since doing so could constitute an inducement to complete the transaction.

Lender-required “cash reserves”

This one takes many home buyers by surprise. It isn’t a closing expense, but lenders require that you have so much cash left in savings after all closing costs are paid.

Lenders have a cash reserve requirement to avoid a buyer “closing broke”. They don’t won’t you to end up in an early-term default. This requirement ensures that the borrower will be able to make their payment during the first few months.

The most typical cash reserve requirement is two months. That means that you must have sufficient reserves to cover your first two months of mortgage payments. So if your principal, interest, taxes, and insurance (PITI) come to $1,500 per month, the reserve requirement will be $3,000.

These are not funds that must be deposited with the lender. But the lender must be able to verify that you will have the funds available in a liquid source. These include savings account, checking account, or money market fund—after closing on the property. Generally speaking, they frown on using retirement assets for this purpose, since those funds cannot be easily liquidated.

Summary

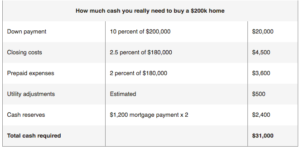

If you are buying a home for $200,000 and need a 10 percent down payment, the total amount of cash that you may need to provide or at least show looks something like this:

As you can see, you could need more than 1.5 times your down payment to successfully close on a house.

That’s why it’s important to include the additional cash requirements in your home buying plans.